At least once in their lives, pipemakers and pipe smokers have been looking up information in the net about Erica arborea (tree heath).

Who has never done it, believe they know enough about it, either due to their long activity in the area, or because they have been sawyers for generations. However, the myriads of pictures, videos and available articles aren’t thorough if not, sometimes, even misleading.

I believe it’s time to add some clarifications to what is already in the net, and to do this I need to dust off my degree in Agricultural Sciences, carefully avoiding the usual data on geographic distribution of the species, botanical characteristics or log preparation. Rather, I’m going to examine some aspects that, to my opinion, may shed a light on some misunderstandings. Let’s see them:

Is heather really male or female?

Is the log part of the stem or of the root?

What purpose has the log to the plant?

Why is it so rare to find flawless briar?

About the first point, in the world of pipes it is commonly spoken about male and female heath. Confusion arises when someone curious decides to ask a considered “expert” what the difference between the two of them is and if both are used to make pipes.

First of all, it is better to clarify that Erica Arboreahasn’t got a sexual differentiation: its flowers are hermaphroditic, because they have both female and male reproductive organs in the same plant.

However, the popular belief to consider some plants as “male” or “female” is rather widespread and often, as in this case, wrong. It is based on the need to distinguish the best plants from the worst ones, for utilitarian purpose only and within the same species, with no real reference to their actual sexual identity.

Now, as the popular believes are suggested by the different regions culture and by the oral transmission of knowledge, it comes out that a different interpretation of the male and female heather concept will correspond to each territory, and which of the two should be better for pipes production. The very few scientific studies on heather mentioning the “male” and “female” distinction are based on the regional definitions. Let’s see, here below, the two most illustrious examples.

From Raffaele Cormio’s monograph, published in 1943 by the magazine “L’ ingegnere” .

(…) Erica arborea L. is commonly referred to also as male broom, to distinguish it from Erica scoparia L., called female broom. This definition shall not be taken in absolute terms, since either of them are species with hermaphroditic flowers. The male and female definition has been adopted, very likely, to indicate the different log quality provided by the two species; the bigger, more compact and coloured one provided by the male, is actually the only one used to make pipes, while the smaller one of the female plant, being a more modest-sized bush ( 1 meter at the most), isn’t accepted for that use (…)

From Daniel Alexandrian’s monograph, published in 1982 in the magazine “Forêt méditerranéenne”.

(…) In exceptional cases, the log doesn’t show up or grows badly. Those workers harvesting the logs distinguish them between “male” and “female” ones. This difference in shape corresponds with different sources or technical qualities, since only the “female” type is interesting. (The log harvesters) are also able to appreciate “in place” the value of the log before its removal. The subjective discrimination criteria, acquired through observation, might be confirmed and specified through a field-based study. They have made possible to elaborate a standard profile of a workable and a not useable heather. Several ecologic factors influence the growth of the heather logs. The most important are: pH, nature of humus, consistence and depth of the soil, elevation and exposure of the place (atmospheric conditions) (…)

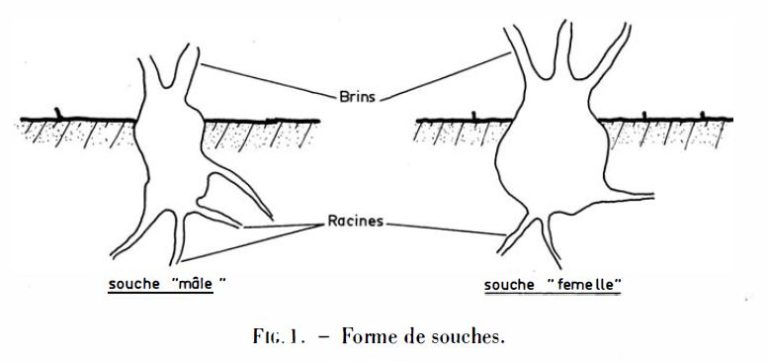

Here is, according to Alexandrien, how we can graphically represent the difference between “male” and “female”:

On the other hand, talking with some still working Italian sawyers, more thesis still come out. Here are just some of the most recurring:

The male has pointing down leaves, the female pointing up. The best log is the female’s;

The male has got just one stem, the female many more. The best stem grows from the male;

The female doesn’t produce a log, the male does;

The male is high, the female is short and bushy. The best log is produced by the male;

And so on…

Who’s right and who’s wrong?

Once it is established that there is no botanical sexual differentiation, I would say everyone, because each region has found its way to distinguish the plant with a good log from that one without or with a bad one.

But is the log part of the stem or of the root? And what is its function to the plant?

The “log”, such a particular irregular wrinkly ball, even lying under the soil, is part of the stemand not of the roots. Considered by some as a tumorous expression of the plant to fungus and insects assaults, it is actually a form of adaptation and specialization of the plant to the lands of its growth, that are rich in complex molecules, minerals as silicon and iron, but poor in nutrients, and it has the specific function to work as a filter (exactly like a kidney), letting in only what the plant can use for its nutrition.

To better understand the concept, let’s imagine we could follow the path of the elements of the soil from the roots to the foliage:

The elements get in contact with the threadlike roots spreading from the log;

Some microscopic fungus (ascomycetes)live tangled up as a ball of yarn within the root cells. They are able to dismantle the complex molecules in the soil, transferring the useful components, through the log, to the plant;

In the meanwhile, most of the silicon and iron are kept by the log.

As we know, it is actually the presence of such a high mineral content that gives the log its remarkable resistance to heat, a characteristic which makes it the top-notch material to realise smoking pipes.

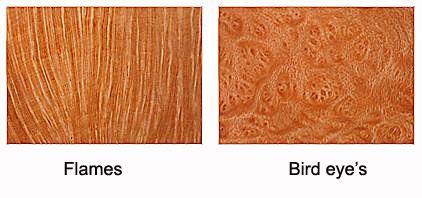

What are exactly the flame patterns and bird’s eyes?

The log has a spherical structure from whose centre, essentially the stem base, countless tubules spread radially. These are the vessels that allow the translocation of the nutrients from the roots to the stem. Therefore, when we cut the log transversely to the tubules, we are going to notice a large quantity of small circles, the so called “bird’s eye”, that are nothing but the visible section of the tubules. If we cut longitudinally to the tubules, instead, we are going to notice their own axial section, the so called “flames”.

But why is it so difficult to find flawless rough drafts of briar?

Any sawyer will tell you that the waste percentage is huge and it can vary for different reasons. Anyway, a plausible waste average stands around 70%. That means that out of 100 Kg of log an average 30 Kg of blocks can be saved, ready to be boiled.

Why such enormous quantity of waste?

The log grows in the soil expanding from its centre towards the outside, just like a balloon when blown up.

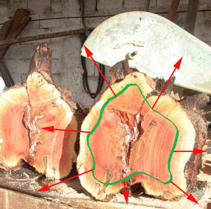

The green marked area in the picture indicates the space occupied by the so called “cambium” (embryonal tissue from which starts the increase in diameter of the stem), where the growth to the outside begins.

The picture shows the situation after several decades from the sprouting of the plant. Initially, when the seed started to produce the plant, the change was along the centre of what would become a log. As the wood expanded in the three dimensions, turning into a spherical shape, the old wood remained there where it had formed, while the new one went on spreading towards the outside (this picture, in particular, shows a big log, deeply damaged in its core and with an intense reddish colour, caused maybe by a strong presence of iron in the soil). During its really very slow growth, the log embeds pebbles, dirt and ashes from old fires, that eventually build up the so called blemishes (to those who don’t know: the Erica arborea is fire resistant, and after a fire it reproduces through root suckers).

In the example initially given, at the end, out of the 30 Kg (average) of the briar saved from waste, 95% will show more or less severe blemishes that are going to determine the choosing of shape and finishing by the pipemaker. The latter knows perfectly what it means to spend long hours working on a promising piece or briar that, at the time of completing the shape, reveals one or more fatal defects, such as cracks or granules of various origins.

So, blessed he, who catches the remaining 5%, because his luck has allowed him to hold in his hands a little jewel on which, anyway, he has had to invest pretty much money.

I hope this in depth-analysis has been of help.

All the pictures have been taken from the net and, when necessary, modified by me. In case I have unwittingly violated copyrighted images, please contact me.